openspace, Nancy, France

And then she said, “You have a future, but it looks a lot like your past” is a collaborative project by Helen Anna Flanagan and Marijke De Roover. The film created by the two artists revolves around the concept of Écriture féminine. This theory examines the relationships between, on the one hand, the cultural and psychological inscriptions of the female body, and on the other hand, the specific characteristics of women’s language and texts. It functions as a way to decenter conventional modes of writing, to claim space, and to bring forth feminist voices in “an ecstatic torrent of words.”

Born from the work of intellectuals, this movement became a cornerstone of French feminist literary theory in the early 1970s. It was especially marked by the publication of Hélène Cixous’ essay “The Laugh of the Medusa” in 1975, featured in an issue of the journal L’Arc dedicated to “Simone de Beauvoir and the struggle between the sexes.” This essay became one of the foundational texts of the second wave of French feminism and, thanks to its English translation, gained a significant international reception that continues to this day.

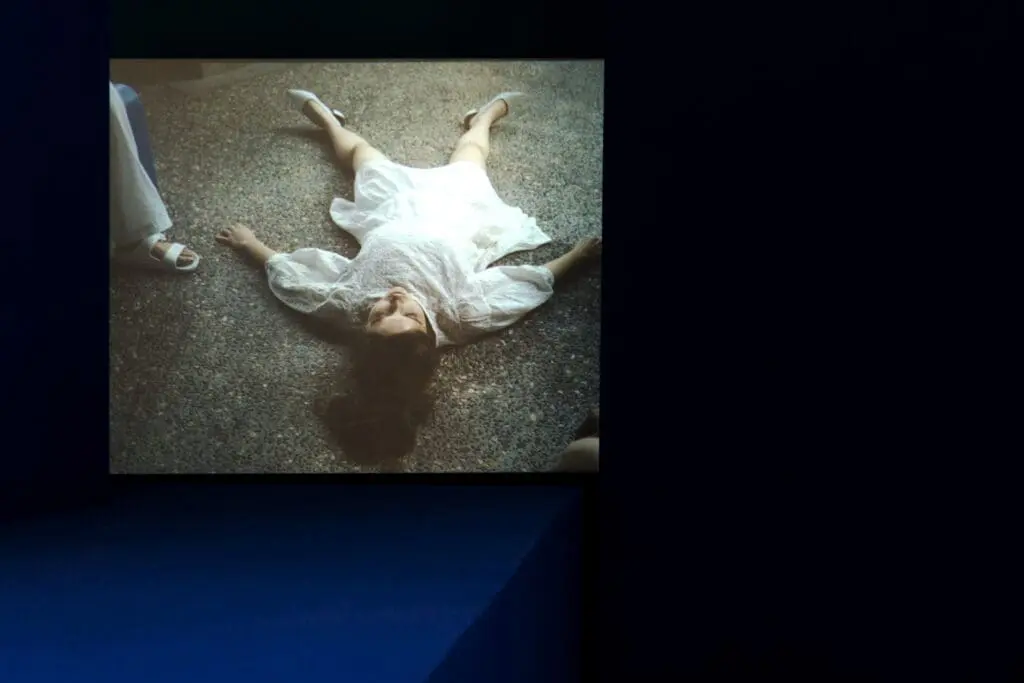

In this text, Hélène Cixous describes writing as “the possibility of change, the space from which a subversive thought can arise, the movement that precedes a transformation of social and cultural structures.” For Cixous, “woman must write herself: must write about women and bring women to writing, from which they have been driven away as violently as they have been from their bodies—for the same reasons, by the same law, with the same fatal goal. Woman must put herself into the text—as into the world and into history—by her own movement.” She must write herself, “because it is the invention of a new, insurgent writing which, at the moment of her liberation, will enable her to bring about the ruptures and transformations necessary in her history.” Writing, she says, is an act that “will not only ‘realize’ the uncensored relationship of woman to her sexuality, to her woman-being, giving her back access to her own powers; it will return to her her goods, her pleasures, her organs, her vast bodily territories held under seal; it will tear her away from the overcoded structure in which she was always assigned the same place of guilt (guilty of everything, always),” because “it is by writing, from and toward woman, and by taking up the challenge of discourse governed by the phallus, that woman will affirm woman differently from the place assigned to her in and by the symbolic order—that is, silence.”

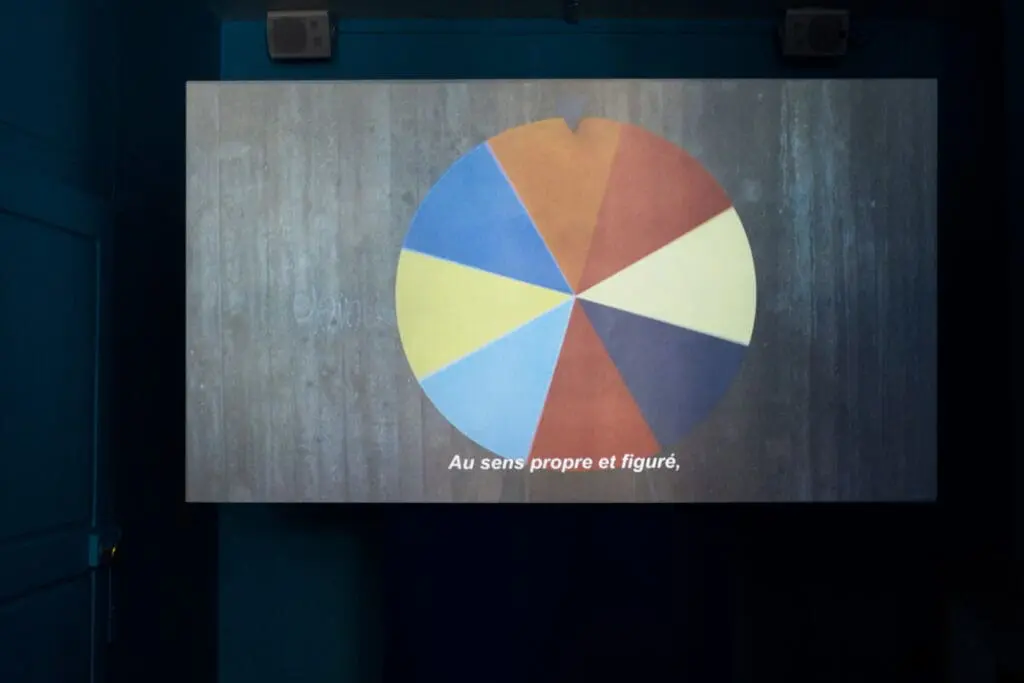

This way of thinking about the relationship between women's bodies and their expression has inspired many female artists and visual practitioners. Hélène Cixous’ text has become “a guiding text in their artistic practice”: “The artists who have responded to the call of the Muse/Medusa work across multiple forms of aesthetic creation; they create new articulations between verbal language and the language of the image, between the artistic work and the female body.” Écriture féminine is thus realized “through movement and projection into space, where the body is from the outset presence, beauty, and provocation.”

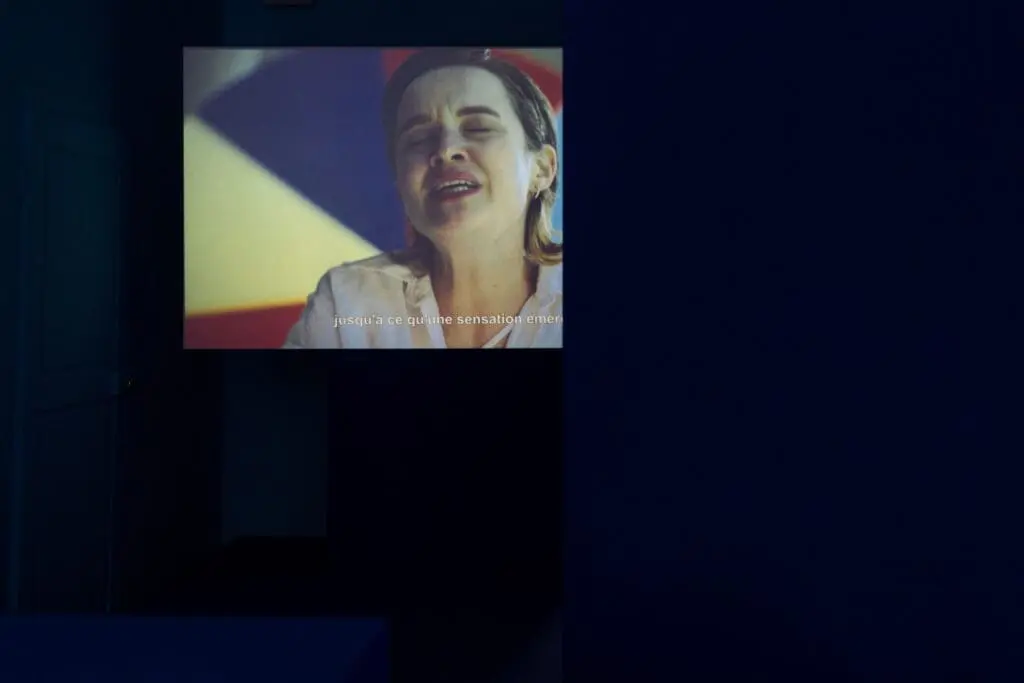

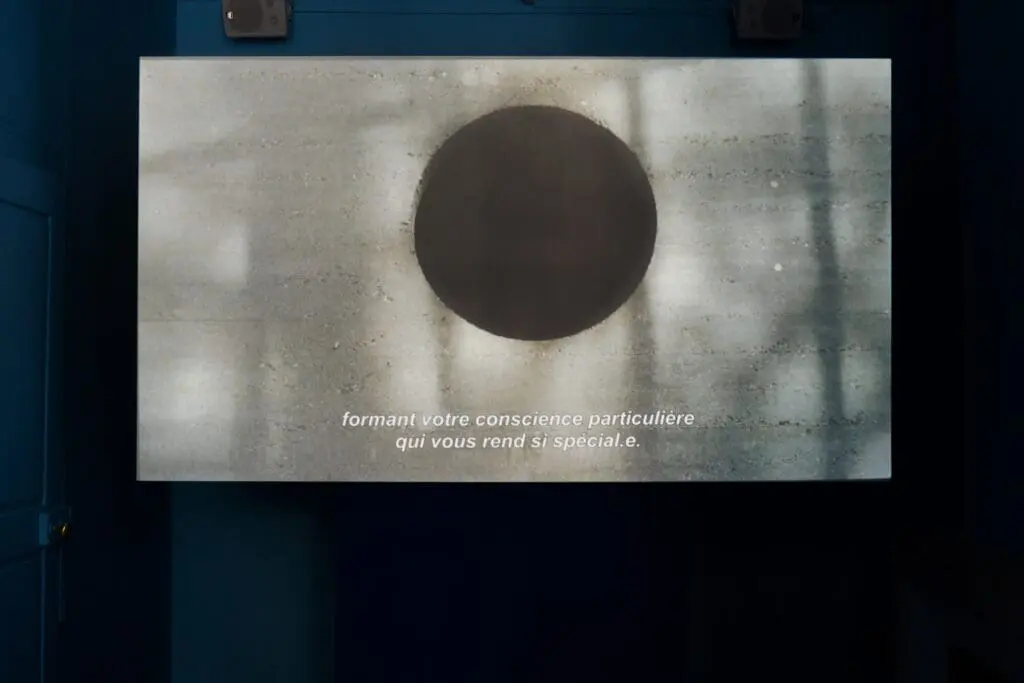

The work of Helen Anna Flanagan and Marijke De Roover aligns with this principle. Six women explore their traumas in a collective, liberatory movement. Within a brutalist architectural setting—referenced in the scenography of the installation—each woman attempts to communicate with the group, to free herself through speech from the intimate wounds caused by the social and societal oppressions she endures. It is in the intertwining of these female and feminist narratives that one glimpses the praxis of Hélène Cixous.

The two artists develop a freedom of association and construction in their screenplay writing. The dialogue interrupts itself, repeats, and overlaps, generating a circulation of the narrative that creates the decentering effect Hélène Cixous calls for—and destabilizes the viewer. There is no linearity in the script—only the desire to express a different kind of speech, unshackled from the patriarchal aesthetic and normative framework.

Yet the conclusion remains a bitter one: society largely remains entrenched in its phallogocentric and heteronormative structures and reflexes. While women’s voices may be liberating themselves, there is still a long way to go before they are truly heard. The future promised by écriture féminine, as declared by Hélène Cixous, still very much resembles our past and present.

Written by Vincent Verlé

Collaboration:

Curator: Vincent Verlé

Supported by:

- Mondriaan Fonds